By Julia Walsh – Patient

By Julia Walsh – Patient

When I was diagnosed in 2013, my treatment options were limited. I saw a community hematology-oncology doctor who told me that I would likely receive FCR, or chemotherapy, as my first line of treatment. And he was correct – the new targeted inhibitors like ibrutinib were several years away from being approved as frontline treatments for CLL patients. As I marched closer to time for treatment, I became concerned and a little bit frustrated at the pace of FDA approval for new treatments for CLL patients. Even though the FDA has dramatically sped up the process in recent years, I watched as the new drugs were approved for relapsed/refractory patients but not for treatment naïve patients like me. It seemed like we were never going to get that frontline approval! Watch and Wait took on new meaning – I was spending time watching the new clinical trial results, and waiting for approval of new drugs. Meanwhile, I had some testing done that revealed my particular flavor of CLL was more aggressive, and that I was expected to need treatment sooner rather than later. I had 11q deletion, and several other mutations that indicated that chemotherapy would not be an effective treatment for me.

I began to think about what my treatment would look like, and what options would work for me and my family. My situation was a little bit complicated because I live an hour plus away from UCSD, where I was seeing my CLL specialist. I still had a teenager at home who relied on me to ferry him back and forth from school, and a dog who needed to be walked and entertained. Like most cancer patients, I was concerned about the burden that treatment would impose on my family.

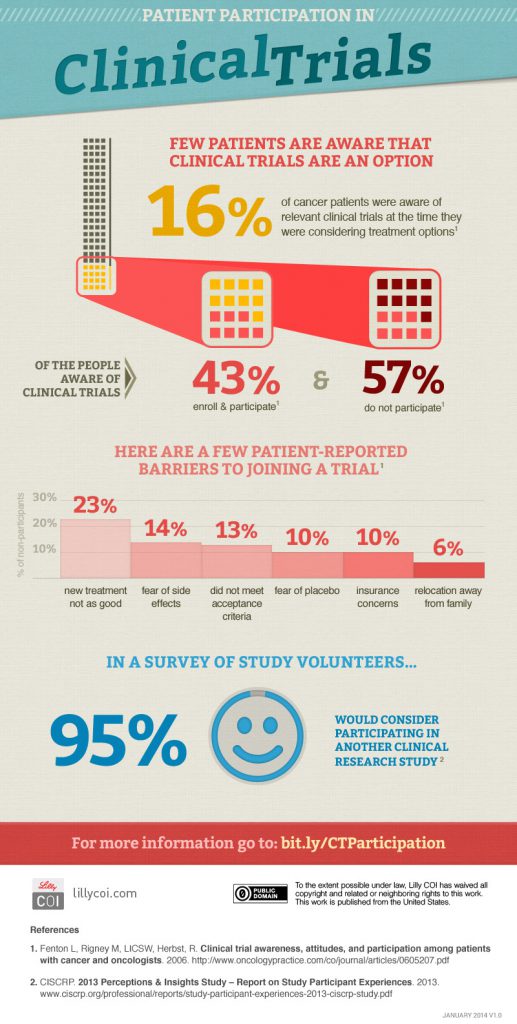

I found when I was talking to friends and family that there were many misconceptions about clinical trials. Many people believed that one arm of the trial would receive a placebo – a drug that would do nothing to treat the cancer. In fact, cancers patients in clinical trials that have two or more arms generally are offered either the standard of care, or the new treatment being studied. Some people believed that insurance would not cover the cost of participation in a clinical trial, when in actuality, federal law requires insurance companies to provide coverage for routine patient care costs. Some people talked about horrible side effects that could occur with new drugs. Although there are no guarantees regarding side effects, I found comfort in the fact that the FDA requires reports of side effects, and is willing to step in and halt the trial when there are safety issues. It was also important to me that the FDA requires researchers to get approval from Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at their institutions. The IRB’s job is to review the study before it begins to make sure that the rights and well-being of the study participants are protected. But I did realize that the lack of accurate information about clinical trials explains why only about 3-6% of cancer patients participate.

Like many CLL patients, I had the luxury of time to decide what I was going to do about treatment. Although my CLL started to get rapidly worse, I still had a few months to decide about treatment. My CLL specialist presented me with several options that included two clinical trials, and since ibrutinib had finally been approved for frontline patients, the possibility of treatment with a new targeted drug outside a clinical trial. We had several appointments where we talked about the pros and cons of each treatment. I was concerned about having to travel to UCSD frequently for the blood draws that were part of the trial, but was relieved when I discovered that many of the routine blood draws could be done at a lab close to my home. Problem solved!

The process of getting qualified for the clinical trial was easy. The financial people at my cancer center worked with my insurance company to get approval. A bone marrow biopsy I had had a few months earlier was still recent enough to be used, so I did not need to get a new biopsy. I had a quick CT scan, had a few tubes of blood drawn, sat down with the clinical trial coordinator to review and sign the detailed consent form, and I was in. And best of all, one of my study medications, ibrutinib, was going to be free for at least the first 3 years of the trial.

Once the trial began, I realized that being in a clinical trial had some very significant benefits. My clinical trial coordinator booked all of my appointments, and sent me reminders. I was very closely supervised and got my monthly exams in the infusion center, which made life easy. My blood values were tracked weekly so I always knew how I was doing. Anytime I had a question or concern, I got an immediate response from my doctor, his nurse or the clinical trial coordinator. I started calling it “concierge medicine” because I felt like a cancer celebrity getting VIP treatment. And best of all, I was happy that no matter what happens with my treatment, I was able to contribute to pushing the CLL treatment landscape forward to help future patients.

To be fair, clinical trials might not be right for everyone. I had a very supportive employer who made it easy for me to take the time I needed for my treatment and my appointments. I was also fortunate to have a caregiver who was extraordinary in the level of support he provided – my husband drove me to every treatment, and never missed a doctor visit. I was lucky to be able to get early data about the risks and benefits of my clinical trial by reviewing American Society of Hematology (ASH) abstracts, which were reassuring because the early results indicated that my clinical trial drug combination was fairly safe. Some patients may not be able to overcome the obstacles of travel and time needed for treatment and appointments, or may not have the information they would like to have to be able to commit to a clinical trial.

My advice to patients who are considering treatment options, though, is to include one or more clinical trials among their options. We are fortunate to have an abundance of clinical trials available worldwide to CLL patients, and no matter where you live there may be a trial close to you. Patients can find information about clinical trials by discussing possible trials with their doctors, searching clinicaltrials.gov or by working with the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s Clinical Trial Nurse Navigator program (https://www.lls.org/treatment/types-of-treatment/clinical-trials). Another great source of information is the CLL Society’s patient support groups, where you will often find other patients who are enrolled in clinical trials and who can discuss the pros and cons. Making treatment decisions is often difficult for CLL patients, but I encourage patients who are ready to start treatment to consider all of their options, including clinical trials, so that they can get the best treatment possible. Just imagine how quickly we could advance CLL treatments if we had more CLL patients in clinical trials.

Julia Walsh JD teaches in the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology. She was diagnosed with CLL in 2013 and has been a patient in a clinical trial at UCSD receiving treatment since 2016. Her passion for research studies prompted her to join the NIH All of Us study, which is designed to improve the use of precision medicine for all patients. Additionally, Julia volunteers with her local high school’s music program.

Originally published in The CLL Tribune Q1 2019.