This is a website about hematology, specifically chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but this article will update research on a significant cardiac condition, atrial fibrillation (AFIB) that is not an uncommon problem for CLL patients and is of particular concern to those on ibrutinib

I will focus mostly on the basic cardiology to help explain the underlying issues.

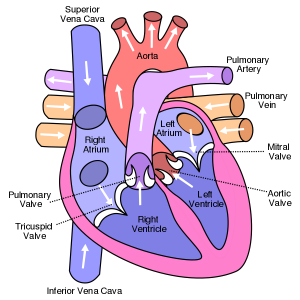

Our hearts have 4 chambers, 2 ventricles and 2 atria.

The ventricles do the heavy lifting with the left ventricle (LV) receiving the oxygenated blood from the lungs via the left atrium (LA), and powerfully sending it coursing through the aorta to the furthest reaches of our body.

The LA does more than provide a little extra kick to the LV to keep the blood moving. Using its sinus node, the heart’s primary pacemaker, it sends the electric signal to the LV to beat. In fact, the usual healthy heartbeat pattern is called normal sinus rhythm (NSR).

If the LA gets enlarged or diseased, then the risk of irregular rhythm increases.

Atrial fibrillation (AFIB) is one such abnormal rhythm that is an increasingly common problem as we age. AFIB is an irregular and uncoordinated contraction of the atrial cardiac muscle. No blood is moved forward in the affected chamber.

When fibrillation affects the LV, this is a true life-threatening emergency, one type of cardiac arrest and is quickly fatal is not immediately reversed. That is why patients are often “shocked” during a “code blue” in order to reverse the fibrillation.

AFIB is not usually such an imminent danger.

But there are still many concerns with AFIB.

The heart is less effective when the LA is not pumping, but this is rarely clinically significant.

AFIB can produce slow or very fast heart rates depending on the ventricle’s response to the AFIB. AFIB is always an irregular rhythm and at times can be dangerously rapid, stressing the blood flow to the heart itself and not allowing the LV to properly fill. This can lead to LV contractions that eject too low a blood volume and even cardiogenic shock where the cardiac output is dangerously inadequate. Slowing the heart rate usually solves that problem even if the AFIB persists.

All doctors are taught this old adage when it comes to AFIB: Control the rate, not the rhythm.

But even if the heart rate is controlled there is a lurking danger.

Since the blood is not moving in the affected chamber, it can clot. If the AFIB then suddenly reverts back to NSR, that contraction of the LA can cause a clot can be ejected or embolized from the heart into the circulation which in turn could cause a life changing stroke and other problems. That is why blood thinners are often used in patients with AFIB, to prevent emboli.

But blood thinners such as Coumadin have their own risks too. Catastrophic bleeding can occur.

The CHAD2 score is a tool that doctors use to help weigh the risk versus benefit of anti-coagulation.

Here is a link to an online CHAD2 calculator.

This is particularly complicated in CLL patients on ibrutinib who develop AFIB, as ibrutinib itself is associated with an increased bleeding risk and those risks can significantly climb when it is taken with a blood thinner, especially with Coumadin.

Fortunately, usually AFIB can be controlled and/or the combination of a blood thinner and ibrutinib can be safely handled when there is an experienced team of hematologists and cardiologists working together.

Still AFIB is the leading side effect that causes patients to stop their ibrutinib.

We do know that the incidence of AFIB is increased in patients taking ibrutinib. We are unsure as to the cause for this association. About 11% of patients will develop AFIB on ibrutinib.

For comparison, in the general population, about 2% of people younger than age 65 have AFIB, while about 9% of those over than 65 years or older have it. The incidence of new cases is only about 0.4%% a year.

Remember that the average age at time of CLL diagnosis is 72. The average age of AFIB in a large German study was 73.

Here is a link to a nice overview of the issue of AFIB with ibrutinib from my interview with Dr. Anthony Mato at iwCLL 2017. The key take-away from that interview is:

- All the patients studied who developed AFIB were able to continue their ibrutinib.

Dr. Anthony Mato and his cardiology colleagues subsequent to that interview published research that found a simple ECG (electrocardiogram) can predict the risk of AFIB in patients considering ibrutinib therapy.

An ECG gives us information about the size of the heart chambers. If the LA is enlarged (LAA), there are telltale findings on the ECG that are easily read by any cardiologist and most primary care providers

Turns out that patients with LAA have a nine-fold higher risk of developing AFIB when on ibrutinib.

Age, high blood pressure, coronary heart disease, diabetes and gender are not predictive.

That said, the authors do not recommend withholding ibrutinib from those CLL patients, just closer follow-up.

Here is a link to that abstract.

This is important research as we increasingly tailor our chronic lymphocytic leukemia therapies to each patient’s need and circumstances.

Stay strong

Brian Koffman, MD

2/13/18