By Larry Marion – Patient

A few days before Thanksgiving in 2005 I was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, discovered by accident during my annual physical — I had no symptoms. In addition to having one of the more common forms of this blood cancer, the extensive blood work found the 11Q deletion.

Fear, panic and disbelief set in, of course. I was in a fog during the initial discussion with my Boston-based hematology oncologist. After returning to our home, I immediately consulted with Dr. Google (thanks, Dr. Brian Koffman, for this nickname). I discovered epidemiology studies from the late 1990s indicated that the median life expectancy of patients with CLL with 11q deletion was between five and six years, with the luckiest patients getting around 10 years post-diagnosis.

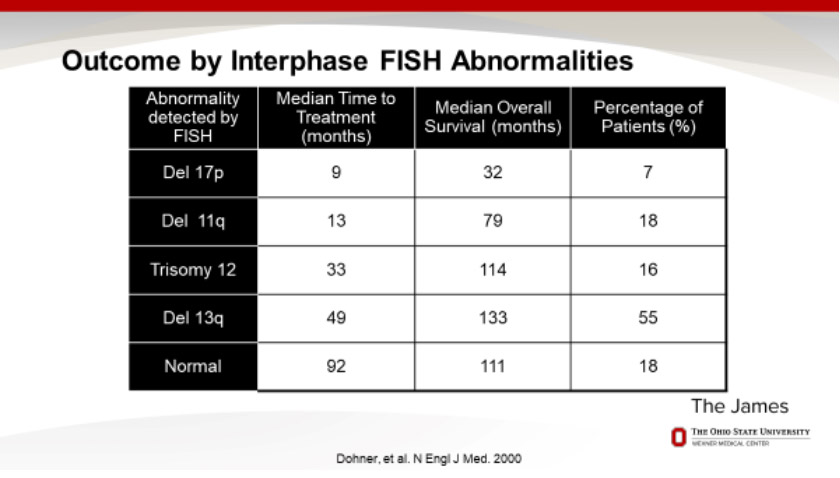

Later clinical history studies found a slight improvement — almost seven-year median life expectancy after diagnosis. The following table (Figure 1) of CLL outcomes by blood factor was prepared by Dr. Farrukh Awan of the Ohio State University in 2017 as part of his presentation “Ask the Expert: The Treatment Landscape for Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia” for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society and was based on a New England Journal of Medicine article from 2000. Note that even way back then, my hem/onc insisted that those data points were obsolete due to new treatments.

Figure 1:The Bad News About 11q and 17p

While I didn’t need treatment as quickly as others with 11q (almost 4 years for me vs. 13 months as the median for other CLL patients with 11q), I was stunned by the survival timeframe.

However, the poor outlook was quite a shock, as you can imagine. I was 55-years-old and otherwise healthy, had a daughter entering high school and had thought that since my parents were healthy and in their eighties, I had a reasonable life span to look forward to. My hem/onc reassured me that those studies had no relation to my outlook, since they were based on patient histories in the distant past and that a host of new technologies and techniques would mean that I would probably die with CLL, not from CLL.

In the meantime, I was told to watch and wait. Like hell! My wife, Leslie Eisenberg, had spent the past 15 years involved in healthcare as a marketing and public relations consultant to pharmas, so she began to dig in. She had found a leading hem/onc in the Boston area, Dr. Ken Miller, thanks to a close friend who is an oncologist.

While I didn’t realize it at the time, Leslie was building a team. Finding additional knowledgeable hem/oncs was crucial — whenever we had any significant medical issue, we always looked for a second opinion. Within a few years the team was assembled. The initial members included:

- My wife, as the note taker, CLL researcher and resolute partner throughout my journey

- My local hem/onc, Dr. Ken Miller of Tufts Medical Center of Boston

- Dr. Adrian Wiestner of the National Institutes of Health. He was leading an NIH clinical history study on CLL. My wife was able to enroll me in the clinical trial, so I would have access to the NIH experts

- Dr. Kanti Rai of Long island Jewish Medical Center. Dr. Rai is a major figure in CLL who had developed a methodology for measuring the progress of CLL as four stages, now known as the Rai scale.

I spent the late 2000s traveling throughout the East Coast, visiting the hem/oncs and watching my blood counts grow.

My lymph nodes began to grow obvious in 2009. Later that year, I was having problems swallowing bulky foods, like bagels. When I mentioned this to my local hem/onc, he looked in my throat and ordered a consult with an ear, nose and throat specialist at Tufts. The ENT found a huge growth in my throat that was partially blocking my esophagus. So, I learned that there are lymph glands in the throat and one of them had swelled to the point that either throat surgery or anti-CLL chemo was required.

The ENT warned that the surgery would remove the lymph gland, but could also ruin my vocal chords. And while my white blood count was only 135k (nowhere near the point that chemo would have been normally indicated), my lymphocyte count was quite high.

Of course, chemo also had serious side effects. So, I consulted with the team. My local hem/onc said I should have the chemo, the PCR cocktail (similar to FCR). I visited Dr. Rai in New York and while I was in the examining room, he called Dr. Miller to discuss my case and whether PCR or FCR was the way to go and whether I should be treated now or later.

Meanwhile, I contacted the hem/oncs at NIH to get their input. The hem/oncs at NIH said I should wait.

While I was debating what to do, and avoiding lumpy foods, an extraordinary event happened. Drs. Rai and Miller met at the ASH meeting in December of 2009. They took some time during the meeting to review my situation. I had no idea they were meeting and discussing my situation until my office phone rang on a Friday morning. It was Dr. Rai calling to tell me that he had met with Dr. Miller at ASH and after discussing the situation he recommended that I should have the PCR chemo.

As long as I live I will never forget Drs. Rai and Miller’s kindness and caring.

The vote was now two to one, so I started PCR in January 2010.

I had seven cycles over the next six months (Figure 2), followed by six months of orally taking a powerful anti-blood cancer agent called Revlimid. Revlimid is a derivative of thalidomide and therefore I had to certify each month I was not having unprotected sex with a fertile woman.

Figure 2: Sitting in a room at the Tufts Infusion Center

I had more hair then….

By 2011, I was in CR based on a bone marrow biopsy (MRD) and luckily had skirted most of the side effects of the chemo. However, I have lasting damage to my immune system and suffer from frequent instances of memory fog, also known as chemo brain. But I was alive and well, living an almost normal life.

Normal until late 2013. The chemo cocktail plus the Revlimid chaser should have lasted five or six years. However, due to 11q, the CLL came back in less than three years. By that time, a new anti-CLL chemo cocktail had been approved by the FDA (bendamustine and rituximab) with fewer side effects, so I had four more chemo cycles. However, 11q again interfered – while the new rounds of chemo in November knocked down the negative CLL blood markers – I still had some physical issues. In other words, it was tough swallowing a bagel again.

Gambling with my life

My doctor wanted me to continue with the traditional chemo, but we became aware of another option. The FDA was a few months away from approving an LLS-funded drug, ibrutinib that appeared to be extremely effective against CLL and 11q. The new oral drug — just take three capsules a day — was described as having relatively minor side effects.

So, I gambled. I decided to wait for the new drug, rather than subjecting myself to more chemo that may not be effective.

I also revised my CLL team. I was no longer in the NIH clinical trial since I had started chemo. My wife arranged for me to become a patient of Dr. John Byrd, the Ohio State University clinician and researcher who was also the principal investigator for ibrutinib.

So, with the blessing of my local oncologist, we traveled to Columbus, Ohio and met with Dr. Byrd. He confirmed that ibrutinib would be a viable alternative. With the blessing of my insurance company, my local oncologist was allowed to write the Rx for the new drug, which was finally approved by the FDA for refractory CLL on Valentine’s Day of 2014. Within a month, the physical symptoms were gone, and my blood levels were looking really good. The side effects appeared to be innocuous (muscle and joint pain and fragile fingernails).

By early in the summer, some bad stuff happened. One of the unusual side effects of ibrutinib is virus activation. I was attacked by a bunch of viruses beginning in mid-June of 2014. I wasn’t able to eat or talk and lost 20 pounds in a matter of weeks, due to a proliferation of mouth sores. I was being driven to the hospital twice a week for tests so that my doc could determine which virus was the problem and prescribe a treatment.

Drs. Miller and Byrd’s offices were in touch about my situation. In addition, I had a series of email exchanges with Dr. Byrd and his team to get their advice about how to treat the various other side effects in addition to the virus activation.

It took several weeks of lab tests for Dr. Miller to find the culprit — Coxsackie virus. The treatment was a series of infusions of gamma globulin (IGG) to help my immune system recover. By the end of July, the virus was on the run, thanks to the eight infusions. I was able to talk, eat, drive and otherwise function. And consuming inordinate amounts of chocolate ice cream!

Unfortunately, the ninth infusion triggered an adverse reaction. Within a half hour of the infusion, my body began vibrating while I was still in the hospital, I was in intense pain and my heart was racing. Remember those dramatic scenes in hospital TV shows when they call for the crash cart or a Code Blue? Well, I had something not nearly as dramatic, but quite scary. The crowd of docs and nurses decided that the best way to stabilize my body was to sedate me.

Four hours later I woke up very sore and very groggy, but fine.

The current scene

I’ve been in remission for more than three years, thanks to ibrutinib and my team. I live a completely normal life, including extensive travel (China, Tibet, Peru) to exotic locales. The photo below (Figure 3) was taken on a sailboat in the Aegean Sea during our visit to Greece.

Figure 3: The outlook—hardly a cloud in the sky

Leslie and I sailing in the Aegean during our trip to Greece

And the outlook for CLL patients is excellent. The hem/oncs use the phrase “durable and long term” to describe my current CLL remission. Even more importantly, Dr. Byrd has a predictive analytic test for patients using ibrutinib that indicates that I am not likely to develop resistance to the drug or suffer transformation/progression to other forms of blood cancer.

Clinical trials underway at OSU and elsewhere are testing anti-CLL cocktails combining ibrutinib and other “novel agents” such as Venetoclax. The theory is that these combos offer the extraordinary hope of not just controlling or managing CLL, but actually curing it.

While many hem/oncs are reluctant to use those words, the level of optimism is amazing, especially considering the history of CLL with 11q or 17p.

A long time ago I was told “If you’re going to get cancer, CLL is the one to get.” It was supposed to make me feel better, but it really didn’t help when I was struggling. And I’m sure you’ve heard the line that you’ll die with CLL, not from CLL.

Well, we may be lucky enough that our obituaries won’t even mention leukemia!

Larry Marion was born and raised in Philadelphia and graduated from Drexel University in 1972, later receiving a master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern University. He spent the first 20 years of his publishing career as a writer and editor for BusinessWeek, Forbes and other business or technology magazines. In 1994 he launched his own publishing company, Triangle Publishing Services Co. In late 2005 Larry was diagnosed with CLL/11q, complex karyotype and unmutated. Last year he started his retirement journey.

Originally published in The CLL Tribune Q1 2018.