By Larry Marion

One afternoon in late March 2013, a group of former colleagues and I were making small talk at a memorial service for Steve, who had just died of a brain tumor. Suddenly Ellen blurted out that she was not only saddened by our friend’s death but also frustrated and disappointed that he hadn’t disclosed his illness beforehand. Ellen, who had told us about her breast cancer diagnosis the year before, lamented that Steve had deprived himself and us of the opportunity to provide support and friendship during his cancer journey.

Her comments stunned me, not just because they seemed self-centered and unsympathetic to his preference to remain silent about his fatal diagnosis. I had been diagnosed with a serious case of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (11q, unmutated, complex karyotype) almost eight years before that conversation. I had told only a few friends and colleagues. In fact, I hadn’t even told my parents.

While I had various reasons for my reluctance, I had never considered the negative impacts of not telling—how family, friends, and long-time colleagues would feel when they learned I had withheld my diagnosis. Furthermore, I had never considered the consequences of late disclosure—from awkwardness to hurt— that would arise in the course of my illness and, luckily, eventual remission.

Ellen’s comments made me reconsider my decision to keep my diagnosis mostly private. Thus, I began my journey to understand better how to disclose this illness. Over time I zeroed in on three big questions that we need to answer when disclosing our CLL:

- Who to tell?

- What to tell?

- When to tell?

as well as the critical follow-up question—how to tell.

To try to answer these questions for other CLL survivors, I offer my lessons learned, and experiences other CLL Society support group members have shared. In addition, I found relevant insights from a 2016 CLL Society survey, some helpful guidance from the American Cancer Society (ACS), and a conversation with one of the blood cancer social workers at Dana Farber Cancer Institute (DFCI) in Boston.

Christina Palis, who has worked with more than 100 CLL patients as an outpatient social worker for blood cancer patients at DFCI, says that disclosure is one of the top five of her patient’s concerns.

Disclosure has also been a frequent discussion topic in the Boston-area support group. We’ve concluded that while it makes sense to share perspectives and experiences, these are such personal and nuanced situations that there is no one right way to disclose (or not to disclose).

Again, it all depends on your situation.

Who to tell?

The ACS has addressed the big questions in a series of essays on its website. For example, one of its articles says that the answers to the first question—Who to Tell? —usually starts with your spouse or significant other, followed by children, followed by close family and friends, and then managers and close colleagues at your employer.

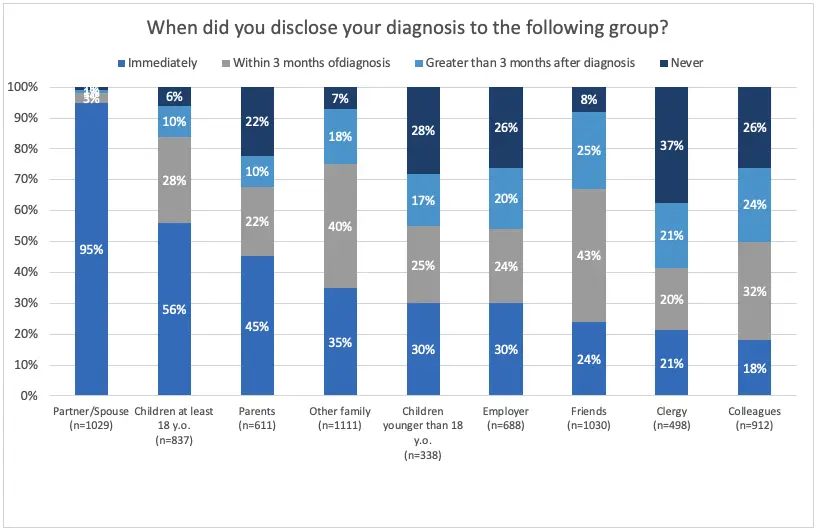

Unpublished data from a CLL Society survey validates this sequence. When asked who they told and in what order, the 1,147 respondents indicated the trickiest groups on that list are children and parents, with a significant number not disclosing their diagnosis to those groups:

Count me in the group reluctant to discuss my diagnosis with their children. Due to her age and other factors, my wife and I had a long debate about what and when to disclose to our daughter just starting high school. Finally, we decided to wait until she was older, when additional information and new meds made my outlook brighter.

However, waiting until you have apparent physical issues or later when you need treatment can have unintended and negative consequences. Delaying disclosure can add hurt on top of concern and could add an element of distrust to the family dynamic. In addition, the late disclosure deprives the family of the opportunity to process the news together. Enabling children to process this potentially devastating news is important–when you tell your children, make sure they have peer resources to share their concerns.

As for discussing this diagnosis with parents, you’ll have to deal with the biggest fear of parenthood—burying a child. Most CLL patients are diagnosed as seniors, so this may not be an issue. But if you’re lucky enough to have living parents, then emphasize the positive outlook.

In my case, I made a deal with God regarding disclosure to my parents. I was diagnosed at a relatively young age—55—and my parents were not only alive but relatively healthy. I decided not to disclose my problem because they would be devastated, no matter how much I soft-pedaled the risk. So instead of disclosure, I asked God to spare my parents the pain of learning the hard way by having to bury their child. In return, I promised Him/Her I would do whatever I could to deserve that blessing. We successfully kept the secret for 14 years, even when hiding the side effects of chemotherapy and other meds was difficult. As a result, my parents lived good, happy, and long lives without knowing I had a higher-risk form of blood cancer.

Another aspect of the “who to tell” dilemma is whether and when to contact close friends and neighbors. I had told almost no one in these groups, but that reluctance led to several awkward moments. For example, at one point during my treatment, I needed lab testing three times a week, but I had nasty side effects and was too weak to drive. Also, my wife and daughter were out of town, and a cab/Uber/Lyft was not an option.

I had to call a neighbor or close friend twice and ask them to take me to the hospital. Disclosing the reason why I looked like death warmed over immediately triggered a combination of sympathy and disappointment—while they were glad to help, they deserved to know before I had a crisis. Unfortunately, it appeared I had to tell them. I should have shared earlier.

The question of workplace disclosure requires extreme caution. As you can see from the CLL Society data, a significant percentage of respondents never told colleagues. My own experience shows the hazard of waiting as well as the hazard of disclosure.

I was the CEO of a small custom publishing company. Unlike a CLL patient, I know who runs a financial services company; I didn’t have a fiduciary responsibility to tell my customers, let alone my management team or partners. I withheld information about my diagnosis from my management team for five years until the week before chemotherapy was to begin. I’ll never forget the silence during that conference call (this was way before Zoom and other forms of video chat became standard). I should have had that talk when I knew the treatment plan, prognosis, and other key pieces of information. Waiting until I was about to have poison pumped into my veins left the incorrect impression I was in dire straits.

And disclosure to a few other work friends, partners, and major clients soon led to “bad” news traveling throughout the industry, to my chagrin. Some clients still wondered whether it was a good idea to do business with my company and me since they were unnecessarily worried whether I would be around to complete their projects. I know I lost some business via indirect and incomplete disclosure. I learned the hard way that when you say the word cancer to colleagues, partners, and clients, some will literally and figuratively keep their distance.

What to say and when to say it

First and foremost, it’s essential to consider whether you know enough to disclose your diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plan to a particular audience. Suppose you’re considering telling family or close friends. Have you considered how they may be needed to help you and your family through this process? If you’re thinking about telling colleagues, do you know how your diagnosis and treatment will impact your ability to do your job? Consider the worries and fears they’ll have and prepare your answers accordingly.

Among the unique aspects of CLL to master and then communicate is the Watch and Wait Conundrum. “Watch and wait is a unique emotional experience,” explains Palis, the DFCI social worker. “The anxiety of its chronic nature makes it difficult to adjust emotionally.”

W&W (also known as watch and worry, active monitoring, etc.) is also challenging to explain to family or friends. Explaining that you’re better off waiting until you need treatment than undergoing “early intervention” won’t be easy. You’ll need a solid understanding of the doctor’s reasoning for W&W and possible treatment plans down the road before explaining it to family and friends.

Another unusual aspect of CLL to mention to family members is the question of genetics. There is some evidence that CLL incidence is higher in certain ethnic groups and almost unknown in others. Also, there is some evidence that more than one family member will develop CLL in some of the higher risk ethnic groups, such as Ashkenazi Jews. Definitely discuss this with your heme/onc before discussing it with family. In some cases, you may need to add this bit of information to your disclosure to children and other family members.

Make sure you emphasize the expected prognosis of CLL as a manageable disease. Especially these days, you don’t want to worry people unnecessarily. However, given the great medications and treatment plans now available, it is incumbent on you to present a complete picture.

And if your heme/onc uses the familiar line, “you’ll die with CLL, not from CLL,” you should repeat that to put your diagnosis into context. Indeed, many CLL survivors are expected to have an average life span for their cohort.

I often used that line, telling it to myself and others once I understood that even my high-risk diagnosis was manageable. Thanks to BTK and BCL2 inhibitors ibrutinib, venetoclax, and my care team, my CLL is not limiting my lifespan or lifestyle.

And then there’s the how

Twelve years after my diagnosis, and three years after successfully getting CLL under control with ibrutinib, I decided to go public. I would be part of a fund-raising campaign for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. I chose to disclose my illness to everyone I knew via an email with a link to a campaign donation webpage.

Within 15 minutes of sending the email, my cell phone rang. My friend Jim was calling to alert me that my email address had been hijacked by a scammer trying to get money. Oops. I thanked him for the alert and explained that it was really from me. And I apologized for announcing my illness in a fund-raising email.

While using a mass email to announce my illness as part of a fund-raising campaign may be among the most thoughtless things I’ve ever done, the ACS offers an intriguing approach to part of the problem. It works with a website called caringbridge.com. This website enables cancer patients to set up a secure web-based bulletin board for their family and friends to learn about their diagnosis and treatment updates and otherwise provide an efficient way to keep everyone in the loop.

Final thoughts

Keeping everyone in the loop starts with the conversation with your doctor about what you can and should disclose about your diagnosis and prognosis, perhaps augmented by a chat with a social worker familiar with CLL and conferring with other CLL patients. Since this is among the most personal and important decisions you make about your relationship with your disease, it deserves a lot of research and thought beforehand. Indeed, more than I did.

And always keep in mind that it is your decision about what, who, and when to discuss this.

Larry Marion’s CLL has been undetectable for almost three years after more than nine years of treatment with various types of chemotherapy, ibrutinib, and venetoclax. Before he retired in 2019, he was a technology and business writer for several magazines as well as the founder and CEO of a small, Boston-based publishing company for the high-tech industry. He and his wife live near Sarasota, FL. My wife and daughter contributed enormously to this article, not to mention getting me to uMRD.

Links and Resources

The CLL Society survey that explains the demographics of disclosure question responders:

American Cancer Society guidance on who, what, when, etc.:

Three different ACS documents on discussing cancer with children

The link to the caring bridge website for information sharing

Normal life expectancy, as per the CLL Society’s December 2022 Bloodline